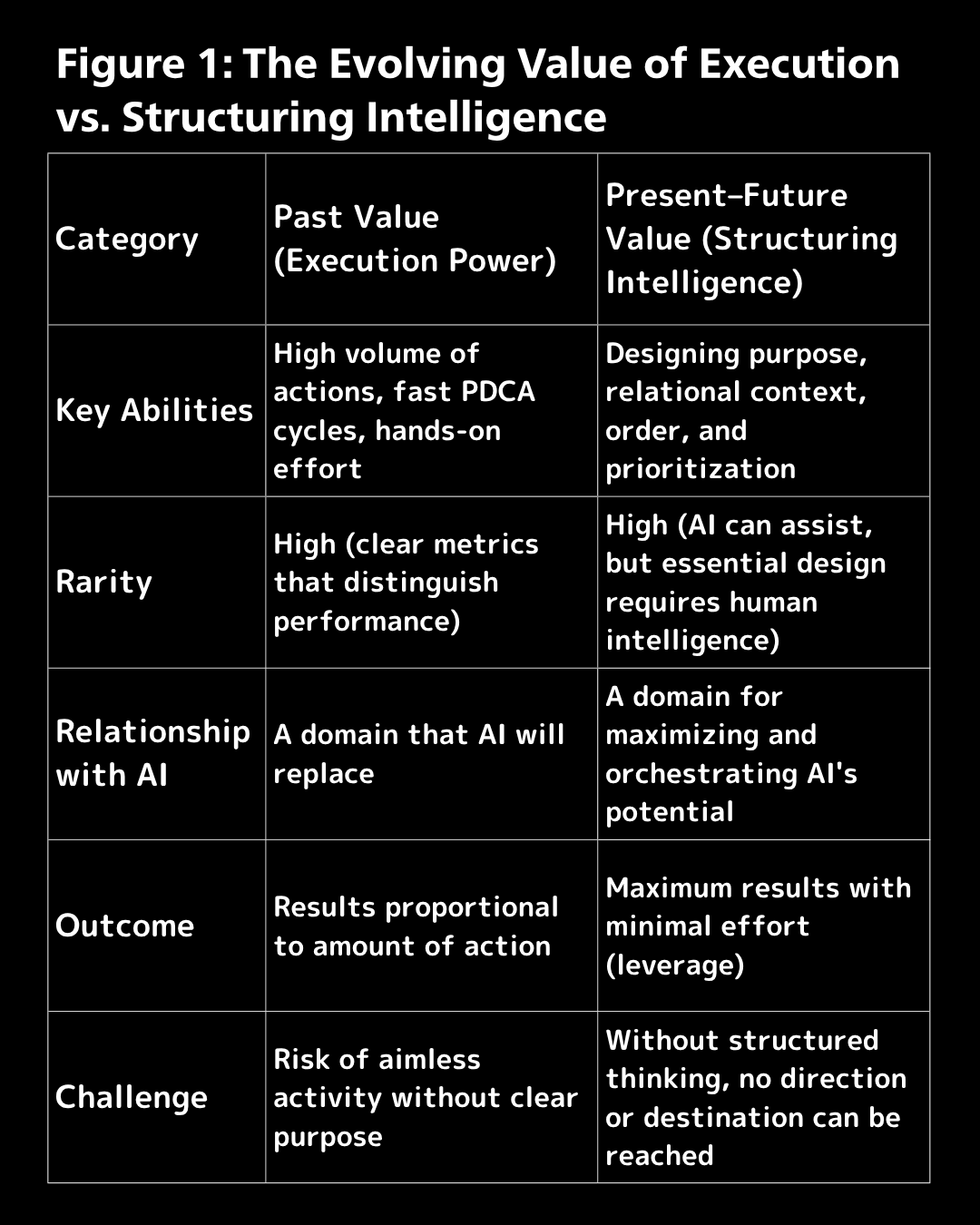

There was a time when execution was one of the most highly valued skills.

How much you could do, how fast you could iterate through PDCA cycles, how persistently you could take action—these were clear indicators of success.

But today, the value of execution is undeniably beginning to shift.

In a world where AI can carry out tasks with speed and precision, many aspects of what was once considered “execution power” are becoming replaceable by machines and algorithms.

Tasks that once required human effort—information gathering, writing, hypothesis-building, analysis, even brainstorming ideas—can now be done in minutes with tools like ChatGPT and other generative AIs.

In other words, “doing” itself is becoming commoditized.

We have entered a world where actions and tasks, once scarce and valuable, are now available in abundance—and often at no cost.

So, what value remains uniquely human in such an era?

The answer lies in the ability to design what should be done—that is, Structuring Intelligence.

As the value of execution declines, the scarcity and importance of structuring power continues to rise. To design structure requires:

- Insight to perceive purpose and relationships,

- Strategic thinking to assemble order and priority, and

- A willingness to confront the core question: “Why does this matter?”

Only those who can create structure can maximize the execution power of AI and others.

Those who cannot draw structure—no matter how hard they work—will find themselves going nowhere.

This is not merely about efficiency.

Action without structure is just motion without meaning.

That is why, in the era to come, the most valuable skill will not be the ability to execute, but the ability to design structure.

This shift represents not just a question of productivity, but a fundamental re-evaluation of human economic value.

If AI can execute faster and cheaper, human comparative advantage will fully move to the pre-execution phase—the ability to define what must be done, and how that fits into a broader, meaningful system.

As a result, we are entering an age where the designer, the one who defines the structure, gains disproportionate leverage.

This change signals not just a shift in labor, but a structural transformation of society.

Traditional execution-focused jobs will decrease, while new roles centered on structure design will emerge.

Educational systems that continue to emphasize producing “executors” may be fundamentally misaligned with the demands of the future, leading to what we might call structural fatigue in society.

The absence of structural thinking is not only an individual problem—it is a systemic one.

Figure 1 visually illustrates this transformation.